As I have lived my life and I will admit I have, and not for any short time so far either...I realize that there are certain things that are an acquired taste, that not every human is fated to appreciate, that in many ways go against a prevailing view of what it is to be "cool" or "popular." The contemporary lieder or song is probably such a thing. In the house I reside in I can guarantee that if I put on such a genre of music I will be subjected to commentary of an unappreciative sort. No less than if I were to play an Albert Ayler recording when he was especially energetic in his expressiveness. It has not stopped me from listening nor will it. I might be wrong about some things but in this case I am sure of myself. I am correct! Some people may hate the late string quartets of Beethoven. Well. It is their loss.

So one is rewarded in the exploration of such musical territory with riches at times, sometimes very exceptionally so, times that make it all worthwhile. I speak today of such a thing, namely composer Mark Abel's new program of World Premier Recordings of his songs, Time and Distance (Delos 3550). These are most definitely songs for our time, Modern surely, not outgoingly in the sense that they are not in an avant garde mode so much as they resound with a most thoroughgoing, advanced harmonic-melodic musicality. They say lyrically something for our time as well. Not sentimental, artful yet not self-consciously so. The words are alternately by the composer, by Kate Gail and by Joanne Regenhardt.

The songs and song cycles, five of them, are set for soprano (Hila Plitmann), mezzo-soprano (Janelle DeStefano), plus piano (Tali Tadmor or Carol Rosenberger) and are joined by percussion (Bruce Carver) on one, organ (the composer) on another. The performances are excellent. Ms. Plitmann to me is especially captivating, but that is not to say Ms. DeStefano is not. She is.

These are songs to grow into. I find them the more sublime the more I listen to this program. There is an endless musicality to them that never grows stale. They are I believe milestones in song for today, and to me very beautiful indeed. So I recommend strongly that you hear then.

Modern classical and avant garde concert music of the 20th and 21st centuries forms the primary focus of this blog. It is hoped that through the discussions a picture will emerge of modern music, its heritage, and what it means for us.

Thursday, August 30, 2018

Monday, August 27, 2018

Trio Accanto, Songs and Poems, Wolfgang Rihm, Aldo Clementi, etc.

If you on the surface came across Trio Accanto's Songs and Poems (Wergo WER 7364-2) without further looking into it, you might assume that this was a music with vocals. If you listened you would find that these are songs and poems without words, a series of five New Music compositions for saxophone (Marcus Weiss), piano (Nicolas Hodges) and percussion (Christian Dierstein).The Trio Accanto as made up in this way is a very accomplished triumvirate of musicians especially gifted in New Music readings and interpretations.

The five compositions complement one another as they exemplify some of the New Music way stations one can appreciate in the music as it is now. And by that I mean music that is not so much a post-something but instead remains the thing itself, albeit farther down the present-day road and where it has taken us. There is a spectrum of soundings from the dramatic and somewhat acerbic edginess of Andreas Dohmen's "Versi Rapportati" which begins the program, to the last work in the sequence, the rather dreamy piece, the quietude of Aldo Clementi's "Tre Ricercar."

The ebbing and flowing sound color variations on the program is helped along by the shifts in the saxophone specifications from work to work, so from alto/baritone for the first piece we follow along in sequence to tenor to contrabass to alto. Piano is a constant, to be joined by a part for celesta in the final work. And percussion varies from sets of various miscellania to vibraphone with or without tubular bells.

All of the works fit comfortably into a more or less High Modern pillowcase as long as you remember that what is High Modern in 2018 is not necessarily the same as it might have been in 1960. So to experience the Dohmen and the Clementi as I mentioned and then in between the Hans Thomalla ("Lied"), the Walter Zimmermann ("As I was Walking I Came Upon Chance"), and the Wolfgang Rihm ("Gegenstuck") is to experience a vibrant, lively and state-of-the-art chamber offering that I know I will return to many times, should I continue to live and prosper in the years to come.

I do recommend this for you who want to stay current with the developments in the world of chamber music in the New Music mode. Bravo!

The five compositions complement one another as they exemplify some of the New Music way stations one can appreciate in the music as it is now. And by that I mean music that is not so much a post-something but instead remains the thing itself, albeit farther down the present-day road and where it has taken us. There is a spectrum of soundings from the dramatic and somewhat acerbic edginess of Andreas Dohmen's "Versi Rapportati" which begins the program, to the last work in the sequence, the rather dreamy piece, the quietude of Aldo Clementi's "Tre Ricercar."

The ebbing and flowing sound color variations on the program is helped along by the shifts in the saxophone specifications from work to work, so from alto/baritone for the first piece we follow along in sequence to tenor to contrabass to alto. Piano is a constant, to be joined by a part for celesta in the final work. And percussion varies from sets of various miscellania to vibraphone with or without tubular bells.

All of the works fit comfortably into a more or less High Modern pillowcase as long as you remember that what is High Modern in 2018 is not necessarily the same as it might have been in 1960. So to experience the Dohmen and the Clementi as I mentioned and then in between the Hans Thomalla ("Lied"), the Walter Zimmermann ("As I was Walking I Came Upon Chance"), and the Wolfgang Rihm ("Gegenstuck") is to experience a vibrant, lively and state-of-the-art chamber offering that I know I will return to many times, should I continue to live and prosper in the years to come.

I do recommend this for you who want to stay current with the developments in the world of chamber music in the New Music mode. Bravo!

Friday, August 24, 2018

Gloria Coates, Piano Quintet, Symphony No. 10

The living US composer Gloria Coates is new to me with today's release. I do note that at the back of the CD booklet several other Naxos CDs are shown covering more of her symphonic and chamber works. I somehow missed them. Never too late of course. So today we have a disk that programs for us her Piano Quintet and her Symphony No. 10 "Drones of Druids on Celtic Ruins" (Naxos 8.559848).

After listening a number of times I find her music original and captivating. Based on the two works presented on the program here long tones are in part a distinctive feature of the music. Not exactly like a Morton Feldman work especially in that there is not-so-much than brown-study quietude that Feldman can do so well. The music can be dramatic and engaged more actively than passively meditative, and there is a full range of dynamics generally speaking.

The Piano Quintet is a four movement, 22 minute exploration of a New Music landscape that does not give us much in the way of rapid bursts of noting so much as it unfolds steadily and articulately in a sort of smoky, misty terrain that evokes and yet nonetheless stays in the foreground as inexorably itself more than a pointing other. Half of the string ensemble is tuned a quarter tone higher than the other so that the landscapes shimmer with unstable drones and slow figuration that is in expressive relief yet is not especially representative as much as abstract. It is good listening.

The Symphony No. 10 evokes the mystery and long-gone silence of a Druidic-Celtic ruin and the subtle echoes of ancient lifeways. Long-tones sprawl outwards and drum rolls perhaps connote loss and longing, and/or maybe a passage of time. Alternately they shape an aural pallet that can be taken in strictly as sound in motion, as a poetry of sound. Growing up as a snare drummer to me a long drum roll has very specific connotations not intended in this music. I unfortunately go back to high school band, where a long drum roll invariably brought on a native suburbian reading of the Star Spangled Banner. This has nothing to do with the music because there is no need to hear that connotation but alas I cannot help it myself. This is mysterious fare and it will get you inside of itself rather quickly. It illustrates readily and aesthetically that nobody in today's music sounds quite like this. Gloria Coates occupies her own special musical space. And you should experience it for yourself I think.

The performances are in the very capable hands of the Kreutzer Quartet and pianist Roderick Chadwick for the Quintet, and the CalArts Orchestra under Susan Allen for the Symphony.

Performances are first-rate. The music takes you to a new place. The Naxos price is an added enticement so why wait?

After listening a number of times I find her music original and captivating. Based on the two works presented on the program here long tones are in part a distinctive feature of the music. Not exactly like a Morton Feldman work especially in that there is not-so-much than brown-study quietude that Feldman can do so well. The music can be dramatic and engaged more actively than passively meditative, and there is a full range of dynamics generally speaking.

The Piano Quintet is a four movement, 22 minute exploration of a New Music landscape that does not give us much in the way of rapid bursts of noting so much as it unfolds steadily and articulately in a sort of smoky, misty terrain that evokes and yet nonetheless stays in the foreground as inexorably itself more than a pointing other. Half of the string ensemble is tuned a quarter tone higher than the other so that the landscapes shimmer with unstable drones and slow figuration that is in expressive relief yet is not especially representative as much as abstract. It is good listening.

The Symphony No. 10 evokes the mystery and long-gone silence of a Druidic-Celtic ruin and the subtle echoes of ancient lifeways. Long-tones sprawl outwards and drum rolls perhaps connote loss and longing, and/or maybe a passage of time. Alternately they shape an aural pallet that can be taken in strictly as sound in motion, as a poetry of sound. Growing up as a snare drummer to me a long drum roll has very specific connotations not intended in this music. I unfortunately go back to high school band, where a long drum roll invariably brought on a native suburbian reading of the Star Spangled Banner. This has nothing to do with the music because there is no need to hear that connotation but alas I cannot help it myself. This is mysterious fare and it will get you inside of itself rather quickly. It illustrates readily and aesthetically that nobody in today's music sounds quite like this. Gloria Coates occupies her own special musical space. And you should experience it for yourself I think.

The performances are in the very capable hands of the Kreutzer Quartet and pianist Roderick Chadwick for the Quintet, and the CalArts Orchestra under Susan Allen for the Symphony.

Performances are first-rate. The music takes you to a new place. The Naxos price is an added enticement so why wait?

Thursday, August 23, 2018

Giulio Briccialdi, Flute Concertos, Ginevra Petrucci, I Virtuosi Italiani

Giulio Briccialdi (1818-1881)? Who? That would have been my response a few weeks ago but no longer. That's because I said OK to a chance to find out what his music sounds like. And so duly arrived in the mail the CD at hand. I've played it enough to know what I very much think, namely that the music is delightful! So we have his Flute Concertos (Brilliant 95767), four to be precise, in a "First World Recording" featuring the limber and accomplished flautist Ginevra Petrucci with the very capable I Virtuosi Italiani.

For the music you might imagine Rossini and the Bel Canto composers along with perhaps an underpinning of Mozart-Haydn? It is firmly classical-era based, operatically melodic, filled with a buoyancy you might well not expect to hear from someone you've never heard before. This music floats like a cake of Ivory Soap, but it does not taste bitter if you try and digest it--not recommended for the soap! (That's why parents washed your mouth out with it. They NEVER would have played Briccialdi instead! Even if they knew of him...) The music is sweetly happy and perhaps only the Italian School of those days got away with such things? It is a matter of discussion, but not here!

So each of the four concertos is a little gem, and not all that little either. The flute parts are brilliant and fit together with the orchestra as a soprano might in an aria, just enough that you cannot mistake the feeling of having been here before, yet never quite like this.

Once you hear this disk a few times you are not surprised to read (in the liners) that Briccialdi started out on flute, which he initially learned from his father. He became famous in his day for his pioneering flute brilliance and his compositions were much appreciated. The flute passages have a very knowing ability to bring out a ringing sonance that Ms. Petrucci takes to heart and capitalizes on. It is a near-perfect meld between composer and flautist I hear and it is a joy indeed to listen to.

So if you want something bubbling upward out of your speakers and you love that Italianate Bel Canto spring in a concerto, and who knew to look for it, this will make you a happy camper I suspect. It is thoroughly of its time and place, but in the very best of ways. Get this if you want to be a little different!

For the music you might imagine Rossini and the Bel Canto composers along with perhaps an underpinning of Mozart-Haydn? It is firmly classical-era based, operatically melodic, filled with a buoyancy you might well not expect to hear from someone you've never heard before. This music floats like a cake of Ivory Soap, but it does not taste bitter if you try and digest it--not recommended for the soap! (That's why parents washed your mouth out with it. They NEVER would have played Briccialdi instead! Even if they knew of him...) The music is sweetly happy and perhaps only the Italian School of those days got away with such things? It is a matter of discussion, but not here!

So each of the four concertos is a little gem, and not all that little either. The flute parts are brilliant and fit together with the orchestra as a soprano might in an aria, just enough that you cannot mistake the feeling of having been here before, yet never quite like this.

Once you hear this disk a few times you are not surprised to read (in the liners) that Briccialdi started out on flute, which he initially learned from his father. He became famous in his day for his pioneering flute brilliance and his compositions were much appreciated. The flute passages have a very knowing ability to bring out a ringing sonance that Ms. Petrucci takes to heart and capitalizes on. It is a near-perfect meld between composer and flautist I hear and it is a joy indeed to listen to.

So if you want something bubbling upward out of your speakers and you love that Italianate Bel Canto spring in a concerto, and who knew to look for it, this will make you a happy camper I suspect. It is thoroughly of its time and place, but in the very best of ways. Get this if you want to be a little different!

Wednesday, August 22, 2018

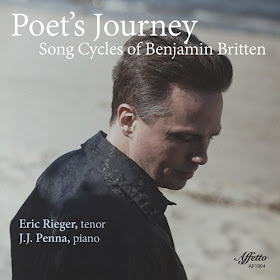

Benjamin Britten, Poet's Journey, The Song Cycles, Eric Rieger

As I get further out from my initial and then ongoing fascination with the music of Benjamin Britten, which began for me around 1984, I realize that his stature slowly grows with me and perhaps with the music world at large despite how he never troubled himself to fit squarely into the paradigm of Modernism the way people tended to understand it around, say the seventies, an important time period for my second formative growth into the appreciation of music as a whole.

It is not that anyone who learns to know his music would mistake what he does for some pre-Modern aesthetic view exactly, for he is of our times as much as anyone. Like for example Melville in literature, he is in the current of his times but as predominantly himself and not as a member of the influences-pooling collective so to say.

Does his gayness have something to do with that? I would say no, not centrally so since Vaughn Williams espoused a similar, rather stubborn individuality in his very own way. (And he was not gay.) Perhaps it is the Englishness that asserts itself in both cases--not so much a nationalism per say but an assertion of identity that is pre-international so to speak.

I feel all of this again as I get familiar with a recent volume of his music, Poet's Journey: Song Cycles of Benjamin Britten (Affetto 1804). Eric Rieger is the tenor for this program, J.J. Penna the pianist. Both are superb in their readings of the Cycles, and you feel a distinctive presence of another vocal approach not so much like Peter Pears, who of course so profoundly took Britten's music on as his own and asserted a way of singing Britten that all who listen deeply to the composer find a part of how they hear the vocal music. And what Rieger does with the cycles is more operatically vibrato-centric, and that is not in the end a bad thing when you become accustomed to it. It is dramatic, certainly, and it surely works on a music level. It is in the end though stylistically slightly apart from the Pears Britten. All well and good.

The three Cycles performed here are substantial and I am glad to get to know them. They consists of "Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo" (1940), "Winter Words" (1956) and "The Holy Sonnets of John Donne" (1945). These are early to mid-period Britten, fully himself, with that trademark synergy of text and tone, that inimitable original organicism one hears with joy in the operas especially.

For those who already love Britten this one would be very welcome, I would think. I feel that way. Those who do not know Britten might do better starting with "Peter Grimes" like I did, but then this is a single volume and self-contained for that. Anyone into the Modern-Contemporary scene would do well to hear this. I am very glad for it myself.

It is not that anyone who learns to know his music would mistake what he does for some pre-Modern aesthetic view exactly, for he is of our times as much as anyone. Like for example Melville in literature, he is in the current of his times but as predominantly himself and not as a member of the influences-pooling collective so to say.

Does his gayness have something to do with that? I would say no, not centrally so since Vaughn Williams espoused a similar, rather stubborn individuality in his very own way. (And he was not gay.) Perhaps it is the Englishness that asserts itself in both cases--not so much a nationalism per say but an assertion of identity that is pre-international so to speak.

I feel all of this again as I get familiar with a recent volume of his music, Poet's Journey: Song Cycles of Benjamin Britten (Affetto 1804). Eric Rieger is the tenor for this program, J.J. Penna the pianist. Both are superb in their readings of the Cycles, and you feel a distinctive presence of another vocal approach not so much like Peter Pears, who of course so profoundly took Britten's music on as his own and asserted a way of singing Britten that all who listen deeply to the composer find a part of how they hear the vocal music. And what Rieger does with the cycles is more operatically vibrato-centric, and that is not in the end a bad thing when you become accustomed to it. It is dramatic, certainly, and it surely works on a music level. It is in the end though stylistically slightly apart from the Pears Britten. All well and good.

The three Cycles performed here are substantial and I am glad to get to know them. They consists of "Seven Sonnets of Michelangelo" (1940), "Winter Words" (1956) and "The Holy Sonnets of John Donne" (1945). These are early to mid-period Britten, fully himself, with that trademark synergy of text and tone, that inimitable original organicism one hears with joy in the operas especially.

For those who already love Britten this one would be very welcome, I would think. I feel that way. Those who do not know Britten might do better starting with "Peter Grimes" like I did, but then this is a single volume and self-contained for that. Anyone into the Modern-Contemporary scene would do well to hear this. I am very glad for it myself.

Monday, August 20, 2018

Enjott Schneider, Magic of Irreality, Isolde & Tristan, Dreamdancers

"We are surrounded by emptiness and dreams," says the composer Enjott Schneider in the liner notes to his recent CD Magic of Irreality (Wergo 5118-2). We are composed bodily of mostly empty space. The solid part of us and the universe is reality energy in motion. Well and good, though on a Monday morning I do prefer to think of the world as very solid, even if that is illusory. I have trouble with the morning coffee, getting it inside me and then dealing with the week! Nonetheless that is in a sense MY problem and nothing to do with the music at hand. And as music can remind us in the best ways, there are seemingly ethereal forces at work always in our life and it can be the best of all of our experiences.

In fact the music in the words of the composer "seek[s] out poetic contradictions," the aerated energy in the illusion of solidity if you will. Imagine Romanticism teetering on the edge of modernism as in ,Wagner's "Tristan" and Schoenberg's "Verklarte Nacht" then add the translucent liquidity of Debussy's "Images" and you may begin the see a picture of the precedents and roots of the two double concertos that comprise this album.

The Siberiun State Symphony under the recently recording rich, ubiquitous conductor Vladimir Lande confidently and artistically present the orchestral tapestries of Schneider with real sympathy and understanding, it seems to me. The soloists for the two concerted works are admirable. For the work "Isolde & Tristan" Jiemin Yan takes the solo erhu part, Wen-Sinn Yang the cello. For "Dreamdancers" it is Otto Sauter on piccolo trumpet and Sergei Nakariakov on the flugelhorn.

"Isolde & Tristan" reverses the order of the characters to underscore Isolde's importance to the story. Solo erhu and cello sound their magic part in expressive ways. Movement one combines motifs from the Tristan prelude especially with music of a Chinese "character," as the composer puts it. The second movement deals with the potion in the story and juxtaposes diatonic Irish inflected melodies of Tristan's homeland with Wagnerian chromaticism. The third movement looks at the night love scene and uses motifs and excerpts from that part of the opera and for the first time the two concerted instruments join in expressive duets. And so the work continues for two more movements and you can hear that and read about it for yourself. Any devotee of this opera will find it all familiar yet reworked and imaginative.

"Dreamdancers" comes into the world of dreams with the night's emotional unrestraint and extra-real unreality. There is much of musical interest to explore here. Distinguished thematic content and a kind of pictoral melodic landscape keep the music in a later tonal mode with the two horns leading the way through the episodic thickets. The horn parts are breathtaking!

See my blog posting from January 3, 2017 for a review of an earlier concerto disk by the composer. I liked that one as well.

Schneider proceeds according to his own dictates and proclivities, and fashions a well-crafted and expressive blend that does not go out of its way to be "Ultra-Modern" yet too would not be mistaken for a work of a composer in say 1900 or so. That indeed is part of the charm, that it comes out of the past to make a singular future for itself.

In the end I appreciate this music. It is neither wildly contemporary nor is it somehow reactionary. This is the music Schneider was born to make, without a doubt, and it grows out of his own musical personality and so is organic I suppose you could say, not in the least ingratiating in a superfluous way. Delightful music, worth hearing.

In fact the music in the words of the composer "seek[s] out poetic contradictions," the aerated energy in the illusion of solidity if you will. Imagine Romanticism teetering on the edge of modernism as in ,Wagner's "Tristan" and Schoenberg's "Verklarte Nacht" then add the translucent liquidity of Debussy's "Images" and you may begin the see a picture of the precedents and roots of the two double concertos that comprise this album.

The Siberiun State Symphony under the recently recording rich, ubiquitous conductor Vladimir Lande confidently and artistically present the orchestral tapestries of Schneider with real sympathy and understanding, it seems to me. The soloists for the two concerted works are admirable. For the work "Isolde & Tristan" Jiemin Yan takes the solo erhu part, Wen-Sinn Yang the cello. For "Dreamdancers" it is Otto Sauter on piccolo trumpet and Sergei Nakariakov on the flugelhorn.

"Isolde & Tristan" reverses the order of the characters to underscore Isolde's importance to the story. Solo erhu and cello sound their magic part in expressive ways. Movement one combines motifs from the Tristan prelude especially with music of a Chinese "character," as the composer puts it. The second movement deals with the potion in the story and juxtaposes diatonic Irish inflected melodies of Tristan's homeland with Wagnerian chromaticism. The third movement looks at the night love scene and uses motifs and excerpts from that part of the opera and for the first time the two concerted instruments join in expressive duets. And so the work continues for two more movements and you can hear that and read about it for yourself. Any devotee of this opera will find it all familiar yet reworked and imaginative.

"Dreamdancers" comes into the world of dreams with the night's emotional unrestraint and extra-real unreality. There is much of musical interest to explore here. Distinguished thematic content and a kind of pictoral melodic landscape keep the music in a later tonal mode with the two horns leading the way through the episodic thickets. The horn parts are breathtaking!

See my blog posting from January 3, 2017 for a review of an earlier concerto disk by the composer. I liked that one as well.

Schneider proceeds according to his own dictates and proclivities, and fashions a well-crafted and expressive blend that does not go out of its way to be "Ultra-Modern" yet too would not be mistaken for a work of a composer in say 1900 or so. That indeed is part of the charm, that it comes out of the past to make a singular future for itself.

In the end I appreciate this music. It is neither wildly contemporary nor is it somehow reactionary. This is the music Schneider was born to make, without a doubt, and it grows out of his own musical personality and so is organic I suppose you could say, not in the least ingratiating in a superfluous way. Delightful music, worth hearing.

Friday, August 17, 2018

Michael Byron, The Ultra Violet of Many Parallel Paths

In music as in life things happen, if you are living in the stream of the present. There will always be new music, and there will be always be older new music, still older new music and then music that is not longer considered new. This is a commonplace. It is obvious. Yet when you live in the stream of it all it is far from commonplace and it is in a way always tempered by the great unknown. What is coming? We cannot know for sure.

Yet we can of course know what has arrived. One of those is composer Michael Byron. If you type his name into the search box in the upper left of this page you will find a number of reviews I have written here. I like what he has been doing. And now I have his recent CD The Ultra Violet of Many Parallel Paths (self released). It is in the form of two longer works for two pianos, performed most ably by Joseph Kubera and Marilyn Nonken. The album was recorded in concert at Roulette Intermedium in New York City late last year.

There is something of the Radical Tonality mode inherent in the music. Then again there arises at times a density that is nearly extra-tonal, but never quite.

This is a kind of process music. It starts at one point and gradually goes to another point and in the doing it changes. Both works have a cascading rhythmic anarchy that is pleasingly stuttered, disjointed, expressive Pollockian scatter and splatter. As each work proceeds it increases in rhythmic density, and there is a kind of post-Cecil Taylor freedom expression there that Free Improv fans will readily find congenial. And New Music ears will have no trouble understanding it as well.

The opening work sets out a quasi-pentatonic-diatonic minor mode in a recognizable scalular pattern that may remind us of Gamelan and other Asian musical sensibilities. Byron then adds additional scalular notes gradually as it becomes more dense and tonally more complex due to simultaneous sounds between the two pianos of scale tones overlapping, creating a kind of increased harmonic consideration.

The second takes to us a kind of whole-tone augmented scalular foundation that splatter-bursts itself from the beginning, that increases in density and continuousness with time and also adds chromatic tones or a chromatic feeling in the midst of the overlap soundings..

The music remains distinct and fascinating no matter how many times you listen. It is very noteworthy, if you'll pardon my pun. I strongly recommend you hear it!

Yet we can of course know what has arrived. One of those is composer Michael Byron. If you type his name into the search box in the upper left of this page you will find a number of reviews I have written here. I like what he has been doing. And now I have his recent CD The Ultra Violet of Many Parallel Paths (self released). It is in the form of two longer works for two pianos, performed most ably by Joseph Kubera and Marilyn Nonken. The album was recorded in concert at Roulette Intermedium in New York City late last year.

There is something of the Radical Tonality mode inherent in the music. Then again there arises at times a density that is nearly extra-tonal, but never quite.

This is a kind of process music. It starts at one point and gradually goes to another point and in the doing it changes. Both works have a cascading rhythmic anarchy that is pleasingly stuttered, disjointed, expressive Pollockian scatter and splatter. As each work proceeds it increases in rhythmic density, and there is a kind of post-Cecil Taylor freedom expression there that Free Improv fans will readily find congenial. And New Music ears will have no trouble understanding it as well.

The opening work sets out a quasi-pentatonic-diatonic minor mode in a recognizable scalular pattern that may remind us of Gamelan and other Asian musical sensibilities. Byron then adds additional scalular notes gradually as it becomes more dense and tonally more complex due to simultaneous sounds between the two pianos of scale tones overlapping, creating a kind of increased harmonic consideration.

The second takes to us a kind of whole-tone augmented scalular foundation that splatter-bursts itself from the beginning, that increases in density and continuousness with time and also adds chromatic tones or a chromatic feeling in the midst of the overlap soundings..

The music remains distinct and fascinating no matter how many times you listen. It is very noteworthy, if you'll pardon my pun. I strongly recommend you hear it!

Thursday, August 16, 2018

Richard Strauss, Eine Alpensinfonie, Frankfurt Radio Symphony, Andres Orozco-Estrada

I've listened to and appreciated the music of Richard Strauss since my high school days. There was a huge spike in his popularity when 2001, A Space Odyssey was released with the "Zarathustra" opening as a key part of the soundtrack, so it was inevitable that a young person opening up to "serious" music for the first time would find Strauss in the course of explorations. So I did. The "Zarathustra," "A Hero's Life," "Eulenspeigel" and in time the operas got my attention and appreciation. "Symphonia Domestica" was a work that I tried on a number of occasions to get into, but for some reason liked well enough but somehow never quite clicked with. The same too with Eine Alpensinfonie (1915). It wasn't that I actively disliked either of these later works. It was only that I failed somehow to grasp them as wholes. Yet I re-listened periodically to the LPs I have had since the early days.

I had the opportunity recently to hear and review a new recording of An Alpine Symphony (Pentatone PTC 5186 628) and I thought, "why not?" So for the last several weeks I have listened to the Frankfurt Symphony under Andres Orozco-Estrada have their way with the sprawling Late Romantic behemoth. To my happy surprise, this time with this version the music suddenly came into focus for me. Partly perhaps I have had some time away from Strauss as a steady diet and so too I am no longer seeking as I hear to compare it with Strauss's earlier tone poems.

And credit must surely be given to the quality of the performances and the audio liveliness here. Orozco-Estrada and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony give the music not just the heroic quality it needs to breathe freely. They give equal weight to the tender retrospection and a tempered passion. Because of all of this I hear the music now as if for the first time. It no longer seems to me a kind of return to "A Hero's Life." Surely it still seems to me in direct relation to that work, but as quite a bit more than a reflexive re-sounding. It is music that stands very well on its own, with no comparison's needed.

Perhaps like Strauss's celebrated "Last Songs" it is an aural equivalent to "older and wiser?" After all, 17 years separate the Alpine from the Hero work. Strauss by then was not quite the cutting edge "Modernist" he was thought to be among New Music devotees at the turn of the century. There were signs that Strauss and the Later Romantic programmatic ways were being supplanted by new tendencies, or we might infer that when looking at what was being created and creating attention or scandal among his contemporaries in those days. Yet this was a work he no doubt felt compelled to create, and surely not as some afterthought.

Time marches on. We no longer need to topple Strauss from the throne of leading-light advances, nor for that matter do we need to restore him to the original sunlight in which he once basked. So too then the Alpensinfonie need no longer be a part of a later horse race. In the end everybody won and nobody won as well. There is a place for the symphony in the gathering of other influential compositions of that era. If we give far more weight to later Mahler than we once did, if we view early Schoenberg and Stravinsky, if we praise Ives and others that nobody knew then, if we look at many composers in more detail and consideration that might have been the case, it does not mean we then dismiss later Strauss. The strife is o'er, the battle done. Nobody really won. And that is all the better for us because it means that much more music we can listen to without regret. So I recommend this recording, very much so.

I had the opportunity recently to hear and review a new recording of An Alpine Symphony (Pentatone PTC 5186 628) and I thought, "why not?" So for the last several weeks I have listened to the Frankfurt Symphony under Andres Orozco-Estrada have their way with the sprawling Late Romantic behemoth. To my happy surprise, this time with this version the music suddenly came into focus for me. Partly perhaps I have had some time away from Strauss as a steady diet and so too I am no longer seeking as I hear to compare it with Strauss's earlier tone poems.

And credit must surely be given to the quality of the performances and the audio liveliness here. Orozco-Estrada and the Frankfurt Radio Symphony give the music not just the heroic quality it needs to breathe freely. They give equal weight to the tender retrospection and a tempered passion. Because of all of this I hear the music now as if for the first time. It no longer seems to me a kind of return to "A Hero's Life." Surely it still seems to me in direct relation to that work, but as quite a bit more than a reflexive re-sounding. It is music that stands very well on its own, with no comparison's needed.

Perhaps like Strauss's celebrated "Last Songs" it is an aural equivalent to "older and wiser?" After all, 17 years separate the Alpine from the Hero work. Strauss by then was not quite the cutting edge "Modernist" he was thought to be among New Music devotees at the turn of the century. There were signs that Strauss and the Later Romantic programmatic ways were being supplanted by new tendencies, or we might infer that when looking at what was being created and creating attention or scandal among his contemporaries in those days. Yet this was a work he no doubt felt compelled to create, and surely not as some afterthought.

Time marches on. We no longer need to topple Strauss from the throne of leading-light advances, nor for that matter do we need to restore him to the original sunlight in which he once basked. So too then the Alpensinfonie need no longer be a part of a later horse race. In the end everybody won and nobody won as well. There is a place for the symphony in the gathering of other influential compositions of that era. If we give far more weight to later Mahler than we once did, if we view early Schoenberg and Stravinsky, if we praise Ives and others that nobody knew then, if we look at many composers in more detail and consideration that might have been the case, it does not mean we then dismiss later Strauss. The strife is o'er, the battle done. Nobody really won. And that is all the better for us because it means that much more music we can listen to without regret. So I recommend this recording, very much so.

Wednesday, August 15, 2018

Stephen Dodgson, String Trios, Karolos

Stephen Dodgson (1924-2013)? I reviewed his 24 Inventions for Harpsichord for this blog on August 17th of 2017, just about a year ago. I liked his tip-of-the-hat to historic forms that nevertheless had a contemporary Modern outlook both original and well wrought. Today we have a new volume of his works, String Trios (Naxos 8.573856). It broadens my view of the composer and gives me an uncompromising series of chamber works for small string ensembles. I believe I am the better for it. Read on to find out if you might be as well.

And what of the composer and his life? The liners help out. He was born in London, served in the Royal Navy during WWII. He then enrolled in the Royal College of Music, subsequently studied composition with Patrick Hadley in Cambridge. Two compositional prizes and a scholarship allowed him to spend several years in Rome, and he returned to London in 1950, where he taught and composed to survive and make himself over in his own musical image. The first String Trio included here marks a high point of his first years.

The music we hear on this program consistently merits close attention. He presents a basically tonal centered yet Modern-edged pallet in the works presented. The String Trios 1 (1951) and 2 (1964) are the main focal points of the program, acting as a kind of sandwich for the three solo string works that contrast nicely enough with the trios.

The solo works have a seriousness of intent and an exploratory mode that marks them as worthy. They cover each one of the three instruments assembled together for the trios. So there is the "Sonatina in B minor for Solo Violin" (1963), the seasonally apt "Caprice after Puck" for solo viola (1978) and the "Partita for Solo Cello" (1985).

Three members of the performing group Karolos provide the fine performances we hear. There is Harriet MacKenzie on violin, Sarah-Jane Bradley on viola and Graham Walker on cello. As players of the solo works they are accomplished and idiomatically appropriate, and as a string trio they excel with a coordinated and briskly brio or a tenderly reflective undulating whole as needed.

Those who gravitate to the serious chamber intimacies of the Modern-Tonal yet expect there to be a consistently intricate edge and would like another twist to a kind of Neo-Classical outlook, seek no further. The world might not move under your feet as you hear this one, but then you will no doubt find the music very well performed and doubtless worthwhile. Four of the five works are in their premier recordings, so this is that place to hear them. And to me they are worth hearing. So.

And what of the composer and his life? The liners help out. He was born in London, served in the Royal Navy during WWII. He then enrolled in the Royal College of Music, subsequently studied composition with Patrick Hadley in Cambridge. Two compositional prizes and a scholarship allowed him to spend several years in Rome, and he returned to London in 1950, where he taught and composed to survive and make himself over in his own musical image. The first String Trio included here marks a high point of his first years.

The music we hear on this program consistently merits close attention. He presents a basically tonal centered yet Modern-edged pallet in the works presented. The String Trios 1 (1951) and 2 (1964) are the main focal points of the program, acting as a kind of sandwich for the three solo string works that contrast nicely enough with the trios.

The solo works have a seriousness of intent and an exploratory mode that marks them as worthy. They cover each one of the three instruments assembled together for the trios. So there is the "Sonatina in B minor for Solo Violin" (1963), the seasonally apt "Caprice after Puck" for solo viola (1978) and the "Partita for Solo Cello" (1985).

Three members of the performing group Karolos provide the fine performances we hear. There is Harriet MacKenzie on violin, Sarah-Jane Bradley on viola and Graham Walker on cello. As players of the solo works they are accomplished and idiomatically appropriate, and as a string trio they excel with a coordinated and briskly brio or a tenderly reflective undulating whole as needed.

Those who gravitate to the serious chamber intimacies of the Modern-Tonal yet expect there to be a consistently intricate edge and would like another twist to a kind of Neo-Classical outlook, seek no further. The world might not move under your feet as you hear this one, but then you will no doubt find the music very well performed and doubtless worthwhile. Four of the five works are in their premier recordings, so this is that place to hear them. And to me they are worth hearing. So.

Tuesday, August 14, 2018

Jonah Sirota, Strong Sad, Contemporary Chamber Music

I am tired of starting off posts with, "oh, and now for something different!" Monty Python did that better than I can, yet there is truth in the saw. They rung down a stage and rung up another. And on today's Modern music scene, differences really do make a difference. And my inclination naturally is to say that about today's music, because it truly is a kind of breath of fresh air.

I allude to the album Strong Sad by Jonah Sirota (National Sawdust Tracks 2018). A friend sent me a copy and after a few spins I began to seriously get in with the sound. It is a kind of Postmodern tonal chamber music in nearly a Radical Tonality mode. Moody, lyrical, touch driven and flying level to the earth more than flying. And all that seems good the way it is done here.

Jonah Sirota is on viola throughout. He also wrote or co-wrote two of the eight compositions on here. Kurt Knecht is on organ and co-wrote one of the works, Molly Morkoski is on piano, and Nadia Sirota appears as additional violist on the interplay much of the time. Additional composition credits go to Valgeir Sigurasson, Rodney Lister, A. J. McCaffrey, Paola Prestini and Nico Muhly.

Now the musicianship is quite high in level. The sound of the various works-groupings I might say seems "natural." By that I mean it is rather unassuming, I will not say casual because it is most deliberate, but then maybe a good word for it is relaxed. There is nothing in the way of stiffness to be detected in either the works or their performance.

And in the compositions there is a kind of a journey in pomo possibilities, various shades, none of which are unoriginal, nothing patently expected as typical of things too typical. And that is where the intriguing qualitieare, the wayward looks at what have differing amounts of ambiance, cyclicities, lyrical sadness or contemplativeness, melodic spin, viola rich poeticism.

After I had listened a few times I started feeling the pull of this music in earnest. It does not call undue attention to itself. It does not flaunt itself or make presumptuous demands on our attention, though some music does all this and if it is wonderful I hardly mind. Yet this entire program does not try to wow us or create fireworks or even to shock us with some boldness. That's OK. If you buffet in the winds of Modernism enough you might find you need something of a break from the pulling about such listener participation sometimes insists upon. That is when you might put this CD on and bask in the tonal washes, the aural watercolors, pastels and memento mori's in tone.

This one certainly is a sleeper.. And for that reason maybe seems like a sort of rare thing. I cannot say there is an album out there quite like this. I do not hesitate to recommend it to you.

Paul Hindemith, Das Marienleben, Juliane Banse, Martin Helmchen

Paul Hindemith's popularity has never exactly waned since his demise years ago, but there was a time when his music was looked upon by some (unfairly I think) as not advanced enough in the Avant Modern sphere. This is somewhat akin to dismissing Bach because he did not stray into Rococo terrain. At this point what followed Hindemith I would say is in the end no more current than he is, so the whole idea of progress too might as well be discounted. It is irrelevant to our musical outlook in terms of our view of the recent past. So we are free to embrace Hindemith, Reger or even Boris Blacher, or for that matter Zimmermann, or even Stockhausen without resorting to an avant thermometer.

Teleology is a bit passe these days and good for that. The now contested assertion by Victorian anthropologists that the evolution of human culinary art was at last reached with the advent of boiling comes to mind, humorously so. Yet for all that we still make hard-boiled eggs with no regrets, as we also might scramble them too without feeling the least bit old-fashioned, even if nuking everything seemed de rigueur a couple of decades ago.

So it is fitting that there be a new version of Hindemith's Das Marienleben (Alpha 398), the classic Expressionist song cycle based on the poems of Rainer Maria Rilke. The version performed is the revised one completed by the composer in 1948.

And understandably this music-as-recording stands and falls on the merits of the performance. Few would contest the importance of the work itself, at least among Hindemith admirers. Julian Banse is an extraordinarily powerful soprano presence that brings a brilliant bite to the proceedings. So also pianist Martin Helmchen gives the music strongly expressive and committed musical foundations.

It is very much as excellent a performance of Das Marienleben as I have heard. The music is as masterful as any Hindemith wrote, but it takes a sure voice and piano togetherness and a consistently potent expressive power to make such on the surface difficult music become clear and movingly comprehensible. They very much triumph in the doing so. This version should stand as the present-day benchmark for the work for a long time to come.

And so I do strongly recommend this offering. Banse and Helmchen bring incomparable depth to the music.

Teleology is a bit passe these days and good for that. The now contested assertion by Victorian anthropologists that the evolution of human culinary art was at last reached with the advent of boiling comes to mind, humorously so. Yet for all that we still make hard-boiled eggs with no regrets, as we also might scramble them too without feeling the least bit old-fashioned, even if nuking everything seemed de rigueur a couple of decades ago.

So it is fitting that there be a new version of Hindemith's Das Marienleben (Alpha 398), the classic Expressionist song cycle based on the poems of Rainer Maria Rilke. The version performed is the revised one completed by the composer in 1948.

And understandably this music-as-recording stands and falls on the merits of the performance. Few would contest the importance of the work itself, at least among Hindemith admirers. Julian Banse is an extraordinarily powerful soprano presence that brings a brilliant bite to the proceedings. So also pianist Martin Helmchen gives the music strongly expressive and committed musical foundations.

It is very much as excellent a performance of Das Marienleben as I have heard. The music is as masterful as any Hindemith wrote, but it takes a sure voice and piano togetherness and a consistently potent expressive power to make such on the surface difficult music become clear and movingly comprehensible. They very much triumph in the doing so. This version should stand as the present-day benchmark for the work for a long time to come.

And so I do strongly recommend this offering. Banse and Helmchen bring incomparable depth to the music.

Monday, August 13, 2018

Paul and Pauline Viardot, Six Pieces, etc., Reto Kuppel, Wolfgang Manz

I am never one to shy away from the unknown, and of 20th century France I would never avoid learning something new, so I said "Why not?" when I had the chance to hear and review the present recording of the music of Paul Viardot (1857-1941) and his mother Pauline Viardot (1821-1910). The program at hand is a collection of short pieces for violin and piano (Naxos 8.573749). The performances are flawless and expressive, idiomatic in a kind of sophisticated and melodically rich salon style then current in French cosmopolitan circles from a bit before the turn of the century through to the 1920s. So that is to say that there are very French musical elements present in this music, a folksy charm, a tuneful lighthearted depth. For this there is something about this music that is not alien to Chabrier, Satie or Debussy, each in his own way and that means sometimes of course a way divergent somewhat but the Viardots share this with the others while possibly embodying more fully the salon tradition per se.

And who are these Viardots? The back cover of the CD informs us that both were a part of the Garcia family, most notably tenor operatic star Manuel Garcia, who was Paula's father. They were as a result of the father's fame very much a part of the Parisian society. Paul was a violin prodigy, which only increased their fame. Of course now I asked "who?" when I saw the names, but life in time handles fame and obscurity with equal indifference and the point is now the music.

All of the music heard on the program is in World Premier recordings. We get Pauline's "Six Morceaux" for twenty minutes of the eighty-some-odd total. It is very pleasing music, more than mere trifles. The Paul Viardot works take up the bulk of the CD and they are miniaturist salon classics with a good deal of violin expressiveness.

None of this music will set the world on fire, sure. Yet it all fills out a place in our understanding of French modernity by furnishing a good, a very good example of the "mainstream" salon-violin music in the modern era. The more one listens the better one likes it all. Like perhaps Fritz Kreisler's violin miniatures it is worthy and characteristic without being some giant leap forward.

Now if you are a devotee of 20th century French music you will want this. If you want something pleasing without being terribly profound you will want this! And it is nice to hear. I am glad of it. Recommended for all the reasons above. It brings back an age we no longer know much of and for that reason it helps us picture the whole scene!

And who are these Viardots? The back cover of the CD informs us that both were a part of the Garcia family, most notably tenor operatic star Manuel Garcia, who was Paula's father. They were as a result of the father's fame very much a part of the Parisian society. Paul was a violin prodigy, which only increased their fame. Of course now I asked "who?" when I saw the names, but life in time handles fame and obscurity with equal indifference and the point is now the music.

All of the music heard on the program is in World Premier recordings. We get Pauline's "Six Morceaux" for twenty minutes of the eighty-some-odd total. It is very pleasing music, more than mere trifles. The Paul Viardot works take up the bulk of the CD and they are miniaturist salon classics with a good deal of violin expressiveness.

None of this music will set the world on fire, sure. Yet it all fills out a place in our understanding of French modernity by furnishing a good, a very good example of the "mainstream" salon-violin music in the modern era. The more one listens the better one likes it all. Like perhaps Fritz Kreisler's violin miniatures it is worthy and characteristic without being some giant leap forward.

Now if you are a devotee of 20th century French music you will want this. If you want something pleasing without being terribly profound you will want this! And it is nice to hear. I am glad of it. Recommended for all the reasons above. It brings back an age we no longer know much of and for that reason it helps us picture the whole scene!

Eugene Zador, The Plains of Hungary, Budapest Symphony, Mariusz Smolij

In my experience in the States there seemed to be few chances to know the music of Eugene Zador (1894-1977) as I was growing up. I cannot recall thumbing past a Zador section or even much in the way of releases in the old record store classical bins, and that was to me a sure indication of someone's status on the music scene then, for better or worse. His later works addressed Hungarian themes and had a folk-like homespun quality at times without adopting directly any nationalist melodic material. Yet there is real inventive facility, an excellent sonaric command of the orchestra, poise and personality in the musical unfolding.

Or it least that is what I have been hearing in the latest Naxos volume of his music, the first I have had the pleasure to hear. I mean The Plains of Hungary (Naxos 8.573800). It is a program of some seven orchestral works, six in their recorded world premier. Doing the honors is the Budapest Symphony Orchestra MAV as directed by Mariusz Smolij. I can find no fault in the performances. In fact they are enthusiastic and balanced.

The back cover of the CD notes that Zador "fused Classicism with Romanticism." Yes I hear that but there seems also a kind of Hungarian Impressionism at play here as well. A tendency to tone paint, to have a dappled descriptive dimension, this is an aspect of the music that provides more than a sort of Classical-Romantic fuse.

So there is a good mix of the earlier and the later, the Nationalist and the generally descriptive. If you did not know some of Zador's titles you might not always make the Hungarian connection yet you certainly can find some local expression once you look for it. A perfect example is the 1969 "Rhapsody for Cimbalom and Orchestra." It is neither dealing with gypsy cliches nor is it in an abstract zone. And for that it is Zador in a characteristic mode. It is a strength and I suppose there is good reason why this piece of all of them has been previously recorded commercially. But that is not to imply something negative about the rest of the music on this CD.

We get six more works, each in their recorded firsts, the 1965 "Dance Overture," the 1970 "Fantasia Hungarica" for orchestra and a subtle solo contrabass, the title work "Elegie, 'The Plains of Hungary,'" from 1960, then finally the rather chipper 22 minute "Variations on a Merry Theme" (1964), and the finale, the 1961 "Rhapsody for Orchestra." All of the works are in emphatic earnest, all have serious ambitions though they cover moods that range from regretful to jovial. Kodaly is not a huge contrast to Zador yet they are distinct and not easily confusable one with the other if you listen intently. This is not especially a set of works with some depth psychology of a Late Romanticist like Bruckner, say, nor are we hearing a Beethoven-like or Brahms-ish heroism, Mendelssohnian Puck, or not really except perhaps obliquely on "Variations on a Merry Theme," no brashly modern Bartok but more Bartok than not-tok. No Stravinsky Neo-Classical at least as he approached it, no Darmstadtian avantness.

And in the discovery of what Zador is not, by elimination you discover what he is. That is himself. And in order to fully arrive to a Zador landscape you must listen more than once. It is not music that especially jumps out on first hearing and mows you down. It may never exactly mow you at all. Instead it has a kind of expressive alone-ness that invites you to join with it for a time. You do so eventually or I did. And if I do not get an elation, a Maher-esque, heaven-bent elation, nor do I want to weep and laugh uproariously as I might with Berlioz, that is OK. Actually it is a good thing, very good. You do not get deja vu much, if at all. Yet the originality does not hit you over the head either. It is music very well crafted, personally idiomatic, with the kind of classical emotional control of a Haydn, but nothing like Haydn? Surely.

If you want to know the Hungarian Modern period better, Zador certainly should not be missed. This is a good place to start.

Or it least that is what I have been hearing in the latest Naxos volume of his music, the first I have had the pleasure to hear. I mean The Plains of Hungary (Naxos 8.573800). It is a program of some seven orchestral works, six in their recorded world premier. Doing the honors is the Budapest Symphony Orchestra MAV as directed by Mariusz Smolij. I can find no fault in the performances. In fact they are enthusiastic and balanced.

The back cover of the CD notes that Zador "fused Classicism with Romanticism." Yes I hear that but there seems also a kind of Hungarian Impressionism at play here as well. A tendency to tone paint, to have a dappled descriptive dimension, this is an aspect of the music that provides more than a sort of Classical-Romantic fuse.

So there is a good mix of the earlier and the later, the Nationalist and the generally descriptive. If you did not know some of Zador's titles you might not always make the Hungarian connection yet you certainly can find some local expression once you look for it. A perfect example is the 1969 "Rhapsody for Cimbalom and Orchestra." It is neither dealing with gypsy cliches nor is it in an abstract zone. And for that it is Zador in a characteristic mode. It is a strength and I suppose there is good reason why this piece of all of them has been previously recorded commercially. But that is not to imply something negative about the rest of the music on this CD.

We get six more works, each in their recorded firsts, the 1965 "Dance Overture," the 1970 "Fantasia Hungarica" for orchestra and a subtle solo contrabass, the title work "Elegie, 'The Plains of Hungary,'" from 1960, then finally the rather chipper 22 minute "Variations on a Merry Theme" (1964), and the finale, the 1961 "Rhapsody for Orchestra." All of the works are in emphatic earnest, all have serious ambitions though they cover moods that range from regretful to jovial. Kodaly is not a huge contrast to Zador yet they are distinct and not easily confusable one with the other if you listen intently. This is not especially a set of works with some depth psychology of a Late Romanticist like Bruckner, say, nor are we hearing a Beethoven-like or Brahms-ish heroism, Mendelssohnian Puck, or not really except perhaps obliquely on "Variations on a Merry Theme," no brashly modern Bartok but more Bartok than not-tok. No Stravinsky Neo-Classical at least as he approached it, no Darmstadtian avantness.

And in the discovery of what Zador is not, by elimination you discover what he is. That is himself. And in order to fully arrive to a Zador landscape you must listen more than once. It is not music that especially jumps out on first hearing and mows you down. It may never exactly mow you at all. Instead it has a kind of expressive alone-ness that invites you to join with it for a time. You do so eventually or I did. And if I do not get an elation, a Maher-esque, heaven-bent elation, nor do I want to weep and laugh uproariously as I might with Berlioz, that is OK. Actually it is a good thing, very good. You do not get deja vu much, if at all. Yet the originality does not hit you over the head either. It is music very well crafted, personally idiomatic, with the kind of classical emotional control of a Haydn, but nothing like Haydn? Surely.

If you want to know the Hungarian Modern period better, Zador certainly should not be missed. This is a good place to start.

Thursday, August 9, 2018

Buxtehude, Abendmusiken, Ensemble Masques, Olivier Fortin, Vox Luminis, Lionel Meunier

On the occasion of living a life there is always music that fits in and when it does it adds much to the day. There may not be many times I would be called upon to account for these high points, except for on here. So I can say that Dietrich Buxtehude (1637-1707) is a name that I readily associate with such happy times. He started at first like so many in the pantheon as another name that came with strong recommendations, most notably from J.S. Bach himself, who revered his mentor and was not reluctant to praise his music. That in time became increasingly compelling as my astonishment over Bach increased, so I in time began to become acquainted with Buxtehude and the musical brilliance there. By now I always welcome another chance to get acquainted with his output. And so there is a new one, Abendmusiken (Alpha Classics 287). It features Ensemble Masques directed by Olivier Fortin, and Vox Luminus directed by Lionel Meunier in very lovely period performances of eight appealing, masterful works.

The album begins with"Gott ilf Mir..." which reminds us or alerts us to the power of Buxtehude in a minor key! There is gravitas, drama, a huge brooding wonder that few could match out there in those days! And the program proceeds from strength-to-strength.

The works range from Trio Sonatas to full-blown Cantatas, all in the High Baroque manner of the Maestro, contrapuntal and otherwise, carefully crafted and minutely set out with the sort of exacting care that he ever embodied. There is a wealth of music performed brilliantly, a cross-spectrum of Biixtehude that serves readily as an excellent introduction to his music, or for that matter expands your library of the master's works if you have already come some ways along in appreciating him. You cannot go wrong with this one for its breadth and period excellence. So I do not hesitate to recommend it to you.

The album begins with"Gott ilf Mir..." which reminds us or alerts us to the power of Buxtehude in a minor key! There is gravitas, drama, a huge brooding wonder that few could match out there in those days! And the program proceeds from strength-to-strength.

The works range from Trio Sonatas to full-blown Cantatas, all in the High Baroque manner of the Maestro, contrapuntal and otherwise, carefully crafted and minutely set out with the sort of exacting care that he ever embodied. There is a wealth of music performed brilliantly, a cross-spectrum of Biixtehude that serves readily as an excellent introduction to his music, or for that matter expands your library of the master's works if you have already come some ways along in appreciating him. You cannot go wrong with this one for its breadth and period excellence. So I do not hesitate to recommend it to you.

Monday, August 6, 2018

Toshiro Mayuzumi, Samsara, Hong Kong Philharmonic Orchestra, Yoshikazu Fukumura

The music of Toshiro Mayuzumi (1929-1997) stands in a place of singular originality to my mind. I've been listening to his orchestral music for years and I must say I love it. There is a new one, very happily at least for me, and it features the title work Samsara (Naxos 8.573916). The Hong Kong Philharmonic under Yoshikazu Fukumura approach the music with the dash, engagement and vibrance it so much requires, and the works themselves are pretty much typical and idiomatic, with the exception somewhat of the second work, but see below.

So what do we get? The program includes three works, the "Phonologie Symphonique" of 1957, the "Bacchanale" of 1953 and the by-now rather iconic "Samsara" of 1962.

For an old Mayuzumi saw like me the early 1953 "Bacchanale" is very illuminating because it shows a Mayuzumi not entirely set into form but fascinating for that.

If you think of the Varese of "Ameriques" then you can then think of how Mayuzumi and he share something, though each in different ways. Then think of some of Luc Ferrari's works and you have the makings of a school which must no doubt include the Stravinsky of "Rite" and some other works of his, "Agon" for example. It is as much as sort of "Primitivism" as Picasso and his fascination with African masks. And I do not mean that negatively.

There are of course the Minimalists out there and I love some of it to tears! The prototypical Reich-Riley uses repetition kind of cosmically and-or African-Indian-Indonesian trancically? The repetitive cells are relatively short, smear-like and one if everything is right can enter a hypnotic zone and tap ones foot at the same time. Now when done well this sort of thing is extraordinary. When done less well it is less extraordinary and can even become a little bit or. a lot banal! And I do not mean either Reich or Riley.

Mayuzumi on the other had comes from a different place that Stravinsky and Varese more or less set the stage for, and Luc Ferrari also practiced, So that is the art of long-form repetition-variation. One could argue and rightly so that even Sonata Form as a whole assumes repetition and variation, well sure. Mayuzumi's long-form repetition builds more or less complicated cellular motives which he then enacts at emotionally taught moments, repeating and varying them. It is the choice-content of the motives and the way they interact with non-repetitive elements. That is the crux of the matter!

So this volume has a great selection of works well performed. If you do not know Mayuzumi here is how to know him a little. And of course if you do, we have another one that bears up under scrutiny and adds nicely to what you already might know and own. Mayuzumi is an essential Modernist and a most original one to boot. Get this.

So what do we get? The program includes three works, the "Phonologie Symphonique" of 1957, the "Bacchanale" of 1953 and the by-now rather iconic "Samsara" of 1962.

For an old Mayuzumi saw like me the early 1953 "Bacchanale" is very illuminating because it shows a Mayuzumi not entirely set into form but fascinating for that.

If you think of the Varese of "Ameriques" then you can then think of how Mayuzumi and he share something, though each in different ways. Then think of some of Luc Ferrari's works and you have the makings of a school which must no doubt include the Stravinsky of "Rite" and some other works of his, "Agon" for example. It is as much as sort of "Primitivism" as Picasso and his fascination with African masks. And I do not mean that negatively.

There are of course the Minimalists out there and I love some of it to tears! The prototypical Reich-Riley uses repetition kind of cosmically and-or African-Indian-Indonesian trancically? The repetitive cells are relatively short, smear-like and one if everything is right can enter a hypnotic zone and tap ones foot at the same time. Now when done well this sort of thing is extraordinary. When done less well it is less extraordinary and can even become a little bit or. a lot banal! And I do not mean either Reich or Riley.

Mayuzumi on the other had comes from a different place that Stravinsky and Varese more or less set the stage for, and Luc Ferrari also practiced, So that is the art of long-form repetition-variation. One could argue and rightly so that even Sonata Form as a whole assumes repetition and variation, well sure. Mayuzumi's long-form repetition builds more or less complicated cellular motives which he then enacts at emotionally taught moments, repeating and varying them. It is the choice-content of the motives and the way they interact with non-repetitive elements. That is the crux of the matter!

So this volume has a great selection of works well performed. If you do not know Mayuzumi here is how to know him a little. And of course if you do, we have another one that bears up under scrutiny and adds nicely to what you already might know and own. Mayuzumi is an essential Modernist and a most original one to boot. Get this.

Friday, August 3, 2018

Michael Hersch, End Stages Violin Concerto, Patricia Kopatchinskaya

To my mind Michael Hersch has become one of the leading luminaries in High Modernism today. He convinces us that there is plenty of stylistic room at the top for the extension of the tradition into living times--and that he is charting a major foray into the zone with every new work. I am not alone in thinking that. If we needed further indication it has arrived decisively and happily in the major new disk that is upon us, a premier recording of end stages violin concerto (New Focus Recordings FCR 208). The 2015 "Violin Concerto" spotlights Patricia Kopatchinskaja as the solo violinist with the International Contemporary Ensemble in the capable hands of Tito Munoz. "End Stages" (2018) gets the attention of the Orpheus Chamber Ensemble. Both are essential; the final result shows an enlightened pairing.

What the two works do is widen our appreciation of the orchestral/concerted Hersch. Both works relate to one another with a seriality that is pleasing. Do both works have an expressive extremity that reaches out to a potentially menacing hugeness to call attention to the human presence in the universe? I hear that, even if perhaps the feeling is more Rorschachian than objective, it we really can relate feeling reactions absolutely to musical tones. And is there a total objectivity available to us in these matters? Not as far as I know. Not on this level.

The Concerto is meant to commemorate the life and passing of a friend. It was commissioned by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and violinist Kopachinskaja. Some somber lines from two Thomas Hardy poems serve as epigrams. A sculpture by Christopher Cairns, Stanchion, adds a kind of correlate to the music from the second movement onwards. Heroically bleak is perhaps the two words that most occur to me as I hear the work repeatedly. There is at the thickest points of the work a special strings against unstrings dichotomy to the music, with the solo part and the string section forming natural alliances and having the more to say while winds join in most appropriately at any rate but not much on their own so much as in tandem. Patricia takes the part with a muscular poeticism that drives forward the shape of the music and sets the pace that the orchestral groupings emulate and further admirably.

"End Stages" (2016) truly seems to continue the musical discourse set in motion by the concerto. It is a sparser, quieter meta-monstration on death and Hersch seems to lighten the burden of grief just a little to allow the sunlight to shine through the louvers of the wooden screen just enough for us to reclaim the boundaries and borders that mark us off from the "not we." If that seems whimsical to you, listen carefully to the music and you may feel it too, but it does not matter as much as the feelings that this music truly "means." The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra take over the musical chairs for this seven part briefer work.There is nothing lightweight or incidental about this music, but then Hersch happily seems incapable of meaninglessness.

If the music on this program is more bracing than joyful keep in mind that we do not remember, say, the story of Oedipus because it is chipper and warm-hearted! Music like literature need not be grinning at all times from ear-to-ear to involve us in serious openings onto a supra-human terrain. That Hersch can do this with increasing strikingness is a reason to rejoice anyway. We need as a species to do more than talk of walls and witch hunts! Lest we forget what makes us special, get this new volume and listen with care. Yes, there IS the new in New Music. This is one place to find it and hold on to it.

Like the generally unsung Alan Pettersson (1911-1980) there is a certain amount of biographical pain and anguish in Hersch's music. And so perhaps is there a personally quixotically macabre strain in Alfred Hitchcock. All artists put something of themselves in their work, no? We come to recognize it and so we come to understand something of the meaning of it all as we do.

Very strongly recommended for all Modernists who want to know that the journey continues.

What the two works do is widen our appreciation of the orchestral/concerted Hersch. Both works relate to one another with a seriality that is pleasing. Do both works have an expressive extremity that reaches out to a potentially menacing hugeness to call attention to the human presence in the universe? I hear that, even if perhaps the feeling is more Rorschachian than objective, it we really can relate feeling reactions absolutely to musical tones. And is there a total objectivity available to us in these matters? Not as far as I know. Not on this level.

The Concerto is meant to commemorate the life and passing of a friend. It was commissioned by the St. Paul Chamber Orchestra and violinist Kopachinskaja. Some somber lines from two Thomas Hardy poems serve as epigrams. A sculpture by Christopher Cairns, Stanchion, adds a kind of correlate to the music from the second movement onwards. Heroically bleak is perhaps the two words that most occur to me as I hear the work repeatedly. There is at the thickest points of the work a special strings against unstrings dichotomy to the music, with the solo part and the string section forming natural alliances and having the more to say while winds join in most appropriately at any rate but not much on their own so much as in tandem. Patricia takes the part with a muscular poeticism that drives forward the shape of the music and sets the pace that the orchestral groupings emulate and further admirably.

"End Stages" (2016) truly seems to continue the musical discourse set in motion by the concerto. It is a sparser, quieter meta-monstration on death and Hersch seems to lighten the burden of grief just a little to allow the sunlight to shine through the louvers of the wooden screen just enough for us to reclaim the boundaries and borders that mark us off from the "not we." If that seems whimsical to you, listen carefully to the music and you may feel it too, but it does not matter as much as the feelings that this music truly "means." The Orpheus Chamber Orchestra take over the musical chairs for this seven part briefer work.There is nothing lightweight or incidental about this music, but then Hersch happily seems incapable of meaninglessness.

If the music on this program is more bracing than joyful keep in mind that we do not remember, say, the story of Oedipus because it is chipper and warm-hearted! Music like literature need not be grinning at all times from ear-to-ear to involve us in serious openings onto a supra-human terrain. That Hersch can do this with increasing strikingness is a reason to rejoice anyway. We need as a species to do more than talk of walls and witch hunts! Lest we forget what makes us special, get this new volume and listen with care. Yes, there IS the new in New Music. This is one place to find it and hold on to it.

Like the generally unsung Alan Pettersson (1911-1980) there is a certain amount of biographical pain and anguish in Hersch's music. And so perhaps is there a personally quixotically macabre strain in Alfred Hitchcock. All artists put something of themselves in their work, no? We come to recognize it and so we come to understand something of the meaning of it all as we do.

Very strongly recommended for all Modernists who want to know that the journey continues.

Thursday, August 2, 2018

John Harbison, Symphony No. 4, Carl Ruggles, Sun Treader, Steven Stucky, Second Concerto for Orchestra, National Orchestral Institute Philharmonic, David Alan Miller

When a recording project is right on many levels, it simply clicks and if your ears can discern what is happening you are the happy beneficiary. I feel that way with today's album. It features three contrasting "American" orchestral works, American in the sense of USA or for some folks E.E.U.U.

The selection creates a zone where we hear three very compatible yet distinctive approaches to the orchestral arts, none of them less "American" than the others, by simple virtue that all three composers have soaked up the life strains of music in this space, and then gone on to ply their own will upon it all, to make their own something from the matrix.

The National Orchestral Institute Philharmonic under David Alan Miller give us a volume in a projected series of such for Naxos. I should give you the particulars now or risk forgetting what should come first. The album features John Harbison Symphony No. 4, Carl Ruggles Sun Treader and Steven Stucky Second Concerto for Orchestra (Naxos 8.559836).