The unaccompanied string solo work is, along with the string quartet, a locus where composer and performer can convene on the deepest levels, where seriousness of purpose does not generally run up against strong pressure to please large numbers of audiences. We generally look backwards to Johann Sebastian Bach as the lineal forefather of the bare-wires solo works for violin and cello (though he was not chronologically the first so much as the contentual "spiritual founder" so to speak).

In the later eighteenth and early 20th centuries Paganini and Max Reger in different ways made their marks on the post-Bachian dialog of solo violin music. The Modern era found in the unaccompanied violin increasingly an aesthetic platform for deeply intimate expression and an art-for-art's sake ambition to forge a modern musical language both abstract and affective to varying degrees, concentrically and infectiously, if you will.

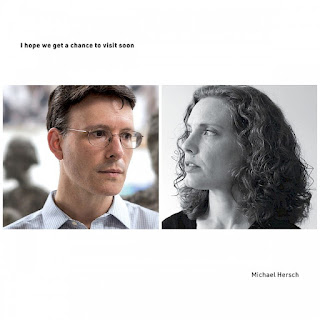

In this light masterful violinist Kinga Augustyn gives us a deeply focused program of Modern unaccompanied violin works on her new album Turning in Time (Centaur CRC 3836). It is a gathering of some six works covering the period from 1958 to 2018. It is a far ranging set of works that call upon the soloist to focus unceasingly, to embrace the ultimate balance point between lateral flow and vertical articulation.

So for example with Luciano Berio's exacting and dramatic "Sequenza VIII" (1976) Ms. Augustyn triumphs in the way she keeps the momentum, the unfolding of the intense line making as she also breezes through and eloquently configures the passages that with hairpin exactitude lay out sequences of multiple stops. We are drawn to key passages that track the music forward, then experience a relative repose before charging forward again.

The Polish compositional phenom Grazyna Bacewicz has been gathering a momentum of recognition in the past few decades and we see why on her 1958 "Sonata No. 2." There is a wonderful Eastern European Modernist logic to the advanced expanded tonality with both consonance and dissonance in the double stops and a remarkably fluid Politsh grace to the line weaving Ms. Augustyn realizes it all with poetic elan and, ultimately, heroic finesse with the rapid multi-stopped virtuoso passagework that jumps out at us towards the end.

A new voice on our horizon is felt and heard with Debra Kaye and her beautiful 2018 "Turning in Time." We feel as we listen at the other side of the Modern Classic juggernaut, having gleaned from dissonance and atonality how a return to key centers is tempered today with a full knowledge of what all possible chromatic combinations and intervals brings to us in potentia, the richness of freedom of possibility. And very appropriately Ms. Kaye gives us a pithy quotation from a Bach Chaconne that reminds us of how far we have come. What Ms. Kaye gives to us is rich yet spare. a giant redwood of potential before there is a leafing, so to say.

Isan Yun further reminds us of the roots when he opens with a theme from Bach's "Art of the Fugue" and proceeds to extend it to a place beyond itself, nicely and with a gravitas that Kinga brings to us wonderfully well.

From there we bounce to a great Elliot Carter work in four parts and some choice Penderecki. All that mounts up no matter where you are in the program's solo legacy.--following the sequence laid out for us or hopping around as I was when I wrote this.

The point is that the whole gives us more than the sum, but then it is a whole that feels just right in terms of our Modernity right now. Then again it gives us a gorgeous snapshot of the warmth, brilliance and intelligence of Kinga Augustyn, a violinist very much at the forefront of today. Bravo!