Modern classical and avant garde concert music of the 20th and 21st centuries forms the primary focus of this blog. It is hoped that through the discussions a picture will emerge of modern music, its heritage, and what it means for us.

Search This Blog

Wednesday, March 30, 2022

Magdalena Hoffman, Nightscapes for Harp

Tuesday, March 29, 2022

Nick Vasallo, Apophany

Tuesday, March 22, 2022

French Connections, Jonathan Rhodes Lee, Harpsichord Music by Louis Couperin, Francois Couperin, Antoine Forqueray

Friday, March 18, 2022

Samuel Adams, Lyra, The Living Earth Show

As I put a can of soup out for lunch just now I noticed the label had on it "New!" Perhaps it is all quite obvious but the exclamation point implies that the newness is a happy thing. One reacts to new things in a myriad if ways of course. But for whatever reason New Music does not often have the idea of an exclamation point attached to it. Partly that is because since the beginning of the 20th century newly composed music often sought (perhaps like never before) to break ground in what music could be, harmonically, melodically, rhythmically and in terms of timbre. And that kind of newness can at first turn off the average music listener in some recent periods of musical history, for it takes a kind of reorientation to listening that requires effort. New soup does not ordinarily ask for much from us. We open the can and off we go--and the manufacturer generally does not try to break ground, to pioneer, for it is supposed generally to be something we expect--chunks of chicken maybe, some noodles and vegetables, nothing radically different. And that is not such a bad idea when it comes to everyday food! We mostly do not thrive on a diet of mink, skunk, grasshoppers and whatever else one might put in one's mouth that is unusual. Eating and art can be two very different things.

New Music on the other hand of course has been dedicated over the years to be something that one way or another was not in our ears or our heads before, or so it can certainly be. So those without a sense of musical adventure might sometimes be wary, for this in its own way can be real work and that is something to scare off some, surely. Yet there are nevertheless a growing number of amenable followers of such newness. They might not be the old lady in the audience that expects Beethoven or something else she already knows. Instead the newbie followers ideally come to the music with an open mind of sorts.

But of course once a certain stylistic kind of newness becomes an accepted or even expected thing in the Modern present-day of whenever it is that you are sitting there in a concert hall, then one's mind is not quite as open as it might be. So for example in the Postmodern Minimalist category or niche there might be a number of paradigmatic possibilities--the sort of NeoRomantic repetition of later Phillip Glass, or the mesmeric post Africanist rhythmic excitement of Steve Reich, or for that matter the pronounced ambient beauty of a John Luther Adams.

As we know these days we should not automatically expect anything that follows a rote procedural unravelling, if we ever quite could. Take for example the young-ish (b. 1985) Samuel Adams, most specifically in the new release of his first full-length album of his work Lyra (Earthy Records EAR-CD-0002).

Lyra (2018-21) was written for the chamber ensemble The Living Earth Show, which features Travis Andrews on guitar, Andy Meyerson on percussion, and the composer on contrabass, piano, moog and electronics. The work itself is meant to be performed live with a specially made film and parts for dancers. The music is put together via something he calls "ambisonic sound design," which I believe involves signal processing in real-time. It is not a radical thing--the instruments themselves sing out with an acoustic authenticity but also an ambient presence.

And of course we realize that good Minimalism, like good anything, is bravely contentual. It does not fear to present itself as itself. And that is exactly what in time becomes clear as you listen. This does not come out of artifice or imitation. This music says itself, completes itself, sings of itself. The nineteen sections all work together and if you are patient, communicate itself to you in ways you understand as not some other, but a musical sister or brother, if you will pardon the florid reaction. Like waiting for spring on a somewhat dull winter's end, you get a shoot, an awakening root, a musical existence that recommends itself to you, then indeed, it delivers.

I say all of this after many hearings. It seemed right to play this one a great deal and now I feel close to it. It is not repetition in some artificial sense, it grows out of itself and is not afraid to change, or then to be the same and change again. There is a very nicely turned trio chamber concept here and you feel as you listen ever closer to its expression.

So I recommend this one heartily. It shows you that a composer of talent can revive and rejuvenate things that we may have begun to take for granted. This is new. In the best sense. Hear it a bunch of times and you will I think get where I am right now with it. Bravo! This is not your ordinary music. It is special! Hear it if you can.

Wednesday, March 9, 2022

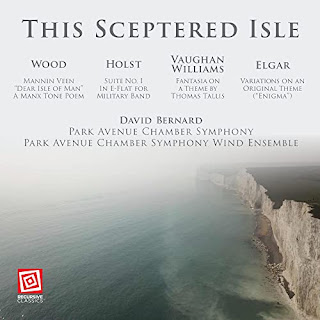

Park Avenue Chamber Symphony and Wind Ensemble, This Sceptered Isle, Music of Wood, Holst, Vaughan Williams and Elgar, David Bernard

So when a new volume of English works of the period arrived at my doorstep the other day, I was glad to see it. It is entitled This Sceptered Isle (Recursive Classics RC5946217) and features the New York based Park Avenue Chamber Symphony and the Park Avenue Chamber Symphony Wind Ensemble, both under the very capable musical directorship of David Bernard.

The program is a balanced selection of two staunchly admired examples of the current standard repertoire, namely Vaughan Williams' "Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis" and Elgar's perennial "Variations on an Original Theme Op. 36 'Enigma'". These are contrasted by two sympathetically treated works a bit less known these days, namely Haydn Wood's "Maunin Veen--'Dear Isle of Man'--A Manx Tone Poem," and Gustav Holst's "Suite No.1 in E-flat for Military Band, Op. 28A."

What the Park Avenue outfit lack in a finished polish they make up for with an articulated enthusiasm that befits the kind of populist earthiness of the music. In this way you might imagine how the premiere performances of these works might have sounded, as something excitingly NEW.

And so also it befits the homespun local and sometimes folkish thrust of the music, especially in my thinking the Wood and Holst works.

The swelling harmonic poignancy of the Vaughn Williams "Fantasia" sounds granularly soaring as well it should. The Elgar "Enigma Variations" has a kind of immediacy that suits the work quite well and every detail is firmly supported by the sureness of sequentiality as is a must for such variations.

And if there are some occasional imperfections in the totality, if sometimes the intonation has a moment or two of slight uncertainty, at the same time this is heartwarming in its singular devotion to making all come alive. There may be better performances of the Elgar and Vaughan Williams out there, but the Wood and Holst works are in scarce supply and these versions give us the whole cloth of where they move into, what a sublime transformation of local strains into the style of Modern Anglo-Symphonism. And as a whole these four works sound like they belong together because they do, they play off against one another and help you understand the parameters of the stylistics then.

And in the end I do recommend this one for its respectable readings of Anglo gems and other works deserving our attention. Hear hear!

Tuesday, March 8, 2022

Ruperto Chapi, String Quartets 1 & 2, Cuarteto Latinoamericano

A month or so ago I reviewed the String Quartets 3 & 4 by Spanish composer Ruperto Chapi (1851-1909) as performed nicely by the Cuartetto Latinoamericano (see review page from February 1, 2022). Happily the record company then sent me the quartet's initial volume of String Quartets 1 & 2 (Sono Luminus DSL-92185). I've been listening to these and I must say they sound every bit as good as the third and fourth ones.

What seems especially noteworthy is the endearing Neo-Classical, vibrantly Spanish melodic rhythmic effervescence of these, almost like a later-day kind of Scarlatti of the Harpsichord Sonatas, something of the captivating Spanish dance-like exuberance. and eloquent spinning of musical tales of those solo works, only not so much imitative as parallel, as a product of the later time period without an excess, without that much of the Romantic sentiment some works of this era of course exhibited. In these works like the later quartets Chapi puts his own personal identity to it like a kind of musical set of fingerprints.

As the program plays repeatedly I grow increasingly happy with how captivating is Chapi's version of the Spanish tinge (as Jelly Roll Morton referred to it). It is distinctive but in every way filled with the kind of forward striving beauty of Spanish earthiness. And as you contemplate this aspect of the music you might realize as I have that Scarlatti and Chapi compare with one another in part as a dual set of nearly timeless qualities of Spanish musical identity. The music in both cases defies when it was written, at least in part.

The liners explore the historical fact that after Boccherini the string quartet in Spain underwent a sort of eclipse in part because there was virtually no string quartets concertizing local works in the country until 1901 and the formation of the Quarteto Frances in Madrid. Ultimately it helped encourage a flowering of the medium in Spain, with post-Romantic works penned by del Campo (some 14), some by Tomas Breton, one by Turina and then the four by Chapi. The liners underscore Chapi's appreciation of Grieg and Tchaikovsky but foremost his immersion in the Spanish vernacular. That makes a bit of good sense of the experience of the Chapi opuses.

The performances seem to me of the benchmark sort, very much brimming over with enthusiasm and vibrancy. And these first two quartets stand out as very worthy of our time and attention. Put all four together in the two volumes and you have something that should appeal to anyone who wants to explore more from the 20th century Spanish realm. I am not giving you a blow-by-blow description of the music as it moves through its assigned movements because I think you will appreciate what it is of course primarily by listening but also because the general ideas I penned here are what will I hope allow you to gauge whether this music is for you. I do recommend it highly. I am happy to have both volumes in my collection. Give this music a hearing if you can. Bravo!

Tuesday, March 1, 2022

Mieczyslaw Weinberg, Sonatas for Violin Solo, Gidon Kremer

When done well, there is something about a modern work for a solo stringed instrument, or for that matter earlier, equally focused ones, like some heartening Bach for violin or cello. In recent years the music of Polish-Russian master Mieczyslaw Weinberg (1919-1996) has been getting at last the attention it deserves as exemplifying an original and compelling compositional voice that extends the legacy of the local brilliances of Prokofiev, Shostakovich, etc. And there is a realization the more we hear it all that he was a real influence, not just somebody who was influenced.

The remarkable Sonatas for Violin Solo (ECM New Series 2705) as played with a brilliant dedication by Gidon Kremer, manages to be a great set of examples of Weinberg's chamber excellence as well as some of the real gems of Modern solo string music. The three sonatas (written in 1964, 1967 and 1979, respectively) combine in Weinberg's special way the simultaneous recurrence of slavic diatonics with interrelated edgy chromatic stridency and tension, all of which ratchets up or down according to the compositional flow..

The release comes to mark Maestro Kremer's 75th birthday and some 40 years collaborating with ECM Records. The care with which Kremer brings this to us in every way helps us celebrate the milestone occasion with the Master.

Kremer gives us highly focused, loving, highly articulated attention to the myriad details and levels of development that the music exhibits so creative-poetically throughout. Kremer in turn expresses an emphatic dynamic and at times a tender playfulness that breaks the music up into contrasting dialogics.

This is extraordinary music in extraordinary performance/ Molto bravo!